Knights and Chivalric orders

Feudal baronies were originally held of the King by military service. The baron was obliged to provide the specified number of knights for the specified period (normally 40 days) when summoned by the King to do so.

Knights, as we know them today were introduced to Scotland by King David I during what is known as the Davidian Revolution. During this time, King David founded the royal burghs, implemented of the ideals of Gregorian Reform, founded of monasteries, Normanized the Scottish government, and introduced feudalism through immigration of Norman and Anglo-Norman knights.

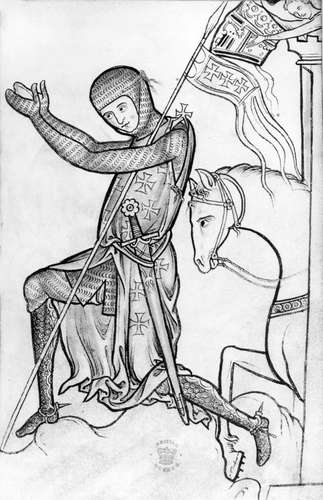

Additionally, the Knights Templar had a presence in Scotland. It began in 1129 after King Henry I of England arranged and introduction of the Templar founder Hugh de Payens to King David I. The Knights Templar were given a parcel of land seven miles south of Edinburgh that became known as ‘Balantrodoch’. They were a part of Scotland until the fall of their order around 1307. It is believed that members of the order were given refuge in Scotland after their dissolution, and some surmise that some fought with Robert the Bruce during the Battle of Bannockburn,

This section will discuss the origins of the knightly class and will showcase some of the lesser-known orders of chivalry and merit from around the world that still exist today.

Becoming a Knight

The first medieval knights were professional cavalry warriors, some of whom were vassals holding lands as fiefs from the lords in whose armies they served, while others were warrior who held no land. The process of entering knighthood often became formalized. First, and aspiring knight would become a page or valet. A young boy served as a page for about seven years, running messages, serving, cleaning clothing and weapons, and learning the basics of combat. He might be required to arm or dress the lord to whom he had been sent by his own family. Personal service of this nature was not considered as demeaning, in the context of shared noble status by page and lord. It was seen rather as a form of education in return for labor. While a page did not receive reimbursement other than clothing, accommodation and food, he could be rewarded for an exceptional act of service. In return for his work, the page would receive training in horse-riding, hunting, hawking and combat – the essential skills required of adult men of his rank in medieval society. At 14, a boy becomes a squire. Squires were the second step to becoming a knight, after having served as a page. Boys served a knight as an attendant or shield carrier, doing simple but important tasks such as saddling a horse or caring for the knight’s weapons and armor. The squire would sometimes carry the knight’s flag into battle with his master.

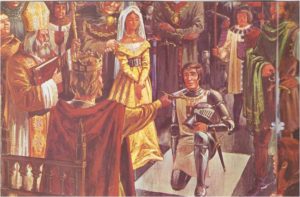

A knight typically took his squire into battle and gave him a chance to prove himself. When he was adjudged proficient and the money was forthcoming for the purchase of his knightly equipment, he would be dubbed knight. The ceremonial of dubbing varied considerably: it might be highly elaborate on a great feast day or on a royal occasion; or it could be simply performed on the battlefield; and the dubbing knight might use any appropriate formula that he liked. A common element, however, was the use of the flat of a sword blade for a touch on the shoulder—i.e., the accolade of knighthood as it survives in modern times.

Age of the knight

As knighthood evolved, a Christian ideal of knightly behavior came to be accepted, involving respect for the church, protection of the poor and the weak, loyalty to one’s feudal or military superiors, and preservation of personal honor. The nearest that the ideal ever came to realization, however, was in the Crusades, which, from the end of the 11th century, brought the knights of Christian Europe together in a common enterprise under the auspices of the church. Knights dubbed at Christ’s tomb were known as knights of the Holy Sepulchre. During the Crusades the first orders of knights came into being: the Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem (later the Knights of Malta), the Order of the Temple of Solomon (Templars), and, rather later, the Order of St. Lazarus, which had a special duty of protecting leper hospitals. These were truly international and of an expressly religious nature both in their purpose and in their form, with celibacy for their members and a hierarchical structure (grand master; “pillars” of lands, or provincial masters; grand priors; commanders; knights) resembling that of the church itself. But it was not long before their religious aim gave place to political activity as the orders grew in numbers and in wealth.

At the same time, crusading orders with a rather more national bias came into being. In Spain, for the struggle against the Muslims there or for the protection of pilgrims, the Orders of Calatrava and of Alcántara and Santiago (St. James) were founded in Castile between 1156 and 1171; Portugal had the Order of Avís, founded about the same time; but Aragon’s Order of Montesa (1317) and Portugal’s Order of Christ were not founded until after the dissolution of the Templars. The greatest order of German knights was the Teutonic Order. These “national” crusading orders followed a course of worldly aggrandizement like that of the international orders; but the crusades in Europe that they undertook, no less than the international enterprises in Palestine, would long attract individual knights from abroad or from outside their ranks.

Between the end of the 11th century and the middle of the 13th, a change took place in the relationship of knighthood to feudalism. The feudal host, whose knights were enfeoffed landholders obliged to give 40 days’ service per year normally, had been adequate for defense and for service within a kingdom; but it was scarcely appropriate for the now more frequent long-distance expeditions of the time, whether crusades or sustained invasions such as those launched in the Anglo-French wars. The result was twofold: on the one hand, the kings often resorted to distraint of knighthood, that is, to compelling holders of land above a certain value to come and be dubbed knights; on the other hand, the armies came to be composed more and more largely of mercenary soldiers, with the knights, who had once formed the main body of the combatants, reduced to a minority—as it were to a class of officers.

From warrior to noble

The gradual demise of the Crusades, the disastrous defeats of knightly armies by foot soldiers and bowmen, the development of artillery, the steady erosion of feudalism by the royal power in favor of centralized monarchy—all these factors spelled the disintegration of traditional knighthood in the 14th and 15th centuries. Knighthood lost its martial purpose and, by the 16th century, had been reduced to an honorific status that sovereigns could bestow as they pleased. It became a fashion of modish elegance for the sophisticated nobles of a prince’s entourage.

A great number of secular knightly orders were established from the late Middle Ages onward: for example, The Most Noble Order of the Garter, Order of the Golden Fleece, The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George, The Most Ancient Most Noble Order of the Thistle, and The Most Honorable Order of the Bath. These honors were reserved for persons of the highest distinction in the nobility or in government service or, more generally, for persons distinguished in various professions and arts. In the United Kingdom, knighthood is the only title still conferred by a ceremony in which sovereign and subject both take part personally. In its modern form the subject kneels and the sovereign touches him or her with a drawn sword (usually a sword of state) first on the right shoulder, then on the left. The male knight uses the prefix Sir before his personal name; the female knight the prefix Dame.

Knightly orders are not unique to the United Kingdom. Many countries from around the globe have created orders based on chivaric ideals as a way to recognize individuals who have distinguished themselves or have provided notable service to the government. Some noteworthy orders have been showcased in this section. See the drop-down menu for specific details.

chivalry

The concept of chivalry in the sense of “honorable and courteous conduct expected of a knight” was perhaps at its height in the 12th and 13th centuries and was strengthened by the Crusades, which led to the founding of the earliest orders of chivalry, the Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem (Hospitallers) and the Order of the Poor Knights of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon (Templars), both originally devoted to the service of pilgrims to the Holy Land. In the 14th and 15th centuries the ideals of chivalry came to be associated increasingly with aristocratic display and public ceremony rather than service in the field.